Dopamine and Stress Response

Dopamine, like norepinephrine, is a neurotransmitter in the brain that initiates adrenalin, a hormone, during the activation of the stress response. The stress response is generally self-regulating, ready to respond to a potential threat and then back down once the threat is lifted. When someone is constantly experiencing environmental stress, this is considered the threat that keeps the stress response system constantly turned on. Leaving the stress response on continuously creates a dangerous and potentially life-threatening condition for the body. This process floods the body with excess hormones, raises blood pressure and elevates blood sugar levels, creating a host physical and psychological problems.

Dopamine, Stress and Locomotion

Dopamine rules motivational forces and psychomotor speed in the central nervous system. Under some stressful conditions, the activity of the stress response system will provide the energy needed to rise to a challenge or be spontaneous. "Focus," a journal of the American Psychiatric Association, suggests that during an event like a sports activity, the role of dopamine and the stress response trigger initiate to spur activity to get the job done and then return to a baseline, or normal, resting level. However, environmental stress such as working in a job that is unpleasant, navigating abusive relationships, financial strain and similarly prolonged events can leave the stress response system on, overworked, and a drain on all other body systems.

- Dopamine rules motivational forces and psychomotor speed in the central nervous system.

- Focus," a journal of the American Psychiatric Association, suggests that during an event like a sports activity, the role of dopamine and the stress response trigger initiate to spur activity to get the job done and then return to a baseline, or normal, resting level.

Dopamine, Stress and Thought-Processing

The Effects of Stress on White Blood Cells

Learn More

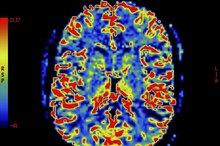

Dopamine and the over-secretion of stress hormones can have multiple effects on the thought-processing function of the brain. Those who are exposed to chronically stressful environments tend to exhibit memory deficits, poor concentration and have inadequate blood flow to the brain. The Franklin Institute suggests that chronic stress and depletion of dopamine in exchange for hormone flooding creates the internal body environment perfect for Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, heart disease and cancer in addition to numerous autoimmune disorders that can be disabling.

Dopamine, Stress and Their Effect

Dopamine dyregulation seen during the stress response can affect our ability to experience pleasure. Excess stress depletes natural dopamine stores and creates a ripple effect on nearby edorphins. The endorphins are necessary to prevent pain and maintain good mood. According to the Franklin Institute, when dopamine and the endorphins malfunction, minor injuries can become major obstacles and experiences of both pain and misery are heightened. Previously enjoyed activities will no longer provide pleasure.

- Dopamine dyregulation seen during the stress response can affect our ability to experience pleasure.

- The endorphins are necessary to prevent pain and maintain good mood.

Dopamine, Stress and Autoimmune Disease

Alcohol's Effects on Adrenal Glands

Learn More

By dopamine instigating the release of stress hormones, the response can turn from good to bad quickly. If the body fails to return to its baseline levels at rest, the long-term consequences of activation can disrupt all organ processes. The "International Journal of Neuroscience" reports that cortisol and other stress hormones lead to chronic inflammation and will negatively impact the skin, cardiovascular, endocrine and digestive systems leaving the body susceptible to diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and cancer. In addition, it can lead to psychological problems related to anxiety, agitation, anger, attention-deficits, learning difficulties, depression, sleep disturbances and permanent memory loss.

- By dopamine instigating the release of stress hormones, the response can turn from good to bad quickly.

- If the body fails to return to its baseline levels at rest, the long-term consequences of activation can disrupt all organ processes.

Related Articles

References

- Carlsson A, Carlsson ML. A dopaminergic deficit hypothesis of schizophrenia: the path to discovery. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(1):137-42.

- Cleveland Clinic. Stress. Updated February 5, 2015.

- Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30(8):1433–1440. doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9606-9

- Stahl JE, Dossett ML, LaJoie AS, et al. Relaxation response and resiliency training and its effect on healthcare resource utilization [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2017 Feb 21;12 (2):e0172874]. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140212. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140212

- American Heart Association. Stress and Heart Health.

- Chi JS, Kloner RA. Stress and myocardial infarction. Heart. 2003;89(5):475–476. doi:10.1136/heart.89.5.475

- Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, González AD, Gabani FL, Andrade SM. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185781. Published 2017 Oct 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185781

- Bitonte RA, DeSanto DJ 2nd. Mandatory physical exercise for the prevention of mental illness in medical students. Ment Illn. 2014;6(2):5549. doi:10.4081/mi.2014.5549

- Ayala EE, Winseman JS, Johnsen RD, Mason HRC. U.S. medical students who engage in self-care report less stress and higher quality of life. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):189. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1296-x

- Richards KC, Campenni CE, Muse-Burke JL. Self-care and well-being in mental health professionals: The mediating effects of self-awareness and mindfulness. J Ment Health Couns. 2010;32(3):247. doi:10.17744/mehc.32.3.0n31v88304423806.

- American Psychological Association. 2015 Stress in America.

- Krantz DS, Whittaker KS, Sheps DS. Psychosocial risk factors for coronary heart disease: Pathophysiologic mechanisms. In R. Allan & J. Fisher, Heart and mind: The practice of cardiac psychology. American Psychological Association; 2011:91-113. doi:10.1037/13086-004

Writer Bio

Robin Wood-Moen began writing in 2000. She is an academic researcher in health psychology, psychoneuroimmunology, religion/spirituality, bereavement, death/dying, meaning-making processes and CAM therapies. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in forensic-social sciences from University of North Dakota, a Master of Science in psychology and is working on her Ph.D. in health psychology, both from Walden University.